Haitian Vodou first took shape in the context of slavery. Once the religion of the royal family in Dahomey, in West Africa, it was then transformed by the slaves of the island of Haiti as a way of restoring a sense of identity and as a force of liberation. This explains the highly significant role played by Vodou in the largest ever successful slave revolt in history and in the creation of an independent Haiti. Initially, anthropology, based on an evolutionary perspective, regarded Vodou as the manifestation of a primitive and barbaric culture closely linked to magic and witchcraft, a view compatible with the European colonisation movement. As a result, Vodou was subjected to a number of waves of persecution by the Catholic clergy. However, over the course of the last decades, anthropology has demonstrated that the syncretism seen in Vodou, notably with its repurposing of the worship of Catholic saints, indicates the creation of a new culture that is capable of tolerance. Its pantheon and its rituals can be understood thanks to an anthropology based on theories of language and symbolic function. Anthropology also shows us that Haitian Vodou serves as a means of remembrance and that it forms part of the patrimony of humanity since the nineteenth century.

Introduction

With its worship of spiritual entities or divinities representing the different domains of nature (water, air, fire, etc.) and human activities (for example, sexuality, work, etc.), Vodou was first practiced in the countries of the Gulf of Guinea, namely Dahomey or present-day Benin, Nigeria, Togo, Guinea, and Ghana. In this area, society was, up until the eighteenth century, largely organised around families, lineages, villages, or ethnic groups. Each of these had their own divinities, referred to as Vodoun, which, in the Fon language in Dahomey, represented an invisible force, capable of manifesting itself in the bodies of certain individuals through trance and possession. Tensions and, in certain cases, wars between ethnic groups favoured a certain mingling on a religious level and some divinities successfully transferred from one ethnic group to another. Particularly in Dahomey, during the eighteenth century, these religions became centralised and were consequently placed under the domination of the royal family.

With the advent of the slave trade (that is to say, the trading of African people) and of slavery which began in the first decades of the sixteenth century, and which intensified partly as a result of the establishment of the French West India Company in 1664, millions of Africans would be deported to the Americas, taking their divinities with them. This led to the emergence of religions such as Candoblé in Brazil, Santeria in Cuba, and Vodou in Saint-Domingue, the French colony which would become the independent state of Haiti in 1804 and then, in 1821, would be divided into Haiti and the Dominican Republic.

Understanding Vodou means first of all focusing on the transformations it underwent as a result of the experiences of Africans originating from many different ethnic groups, who were eager at a very early stage to establish the conditions for their freedom from slavery. Anthropological research will always be haunted, or at the very least intrigued, by the astonishing effort made by the slaves who managed to produce a new religious and cultural system which integrated at one and the same time elements handed down from the various ethnic groups now living together in the same area, those imposed by the institution of slavery, and those handed down from the Amerindians. This intercultural mix of very heterogeneous elements seems to encapsulate the unique nature of Vodou.

Anthropologists often distinguish between two stages in the formation of Vodou in Haiti. The first of these occurred during the period of slavery in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and the second began with the independence of Haiti in 1804 and has continued up to the present day, taking on new forms in a changing political context. By examining the Vodou pantheon and its rituals, this entry will focus its anthropological investigation on the significance of Vodou divinities on individual and collective life. In spite of the prejudices rooted in an anthropology originally based on the opposition between ‘barbarians’ and ‘civilised’ individuals, Vodou will be turn out to be a source for creating a new culture, a place of memory and part of humanity’s universal heritage.

Slavery and the development of Vodou

The living conditions in which the slave trade and slavery had plunged Africans in the Americas made it difficult, if not impossible, to maintain the religious and cultural inheritance of the ethnic groups from which they had originated. Slaves were effectively separated from their families and their lineage and were considered as personal property, and slavery was offered to them, according to most missionaries, as an opportunity to obtain access to the condition of true human beings. Thus, for example, the French Blackfriar Father Jean-Baptiste Dutertre was able to assert that ‘their bondage [was] the principle of their happiness’ and that ‘their disgrace [was] the cause of their salvation’ (1666, 35). At that time, Africa was regarded as a continent peopled by savages and barbarians and afflicted by what was then referred to as ‘the curse of Ham’, a legend based on the Biblical story of Canaan and his sons, and in particular Ham who was declared ‘cursed’ and destined for slavery. The same legend attributed black skin to Ham, and would be used, from the seventeenth century onwards, notably in Holland in 1666, as justification for the trade in and enslavement of Africans.

Conversion to Christianity would therefore lead to the gradual cultural assimilation of the African slave. Emerging in the eighteenth and nineteenth century, anthropology (see Duchet 1971) was dominated by an evolutionary perspective which saw Europe as the pinnacle of humanity, in contrast with Africa which was considered to be at the lowest point of the hierarchy.

The publication of the Code noir (‘Black code’) by French king Louis XIV in 1685 sought to legitimise the practice of slavery after the revocation of the Edict of Nantes. Enacted in 1598, the latter effectively brought an end to the wars of religion in Europe by establishing civil and religious peace. By revoking the Edict, Louis XIV made it possible to include in the preamble to the Code noir intolerance towards Protestantism and Judaism and an order to baptise and instruct slaves in the Catholic religion. Article 2 of the Code noir stipulates: ‘All the slaves that shall be in our islands shall be baptised and instructed in the Roman, Catholic, and Apostolic Faith.’ Article 3 states: ‘We forbid any public exercise of religion other than the Roman, Catholic, and Apostolic Faith…’ (Sala-Molins 1987). This was a reference to both Protestant and Jewish religions. But as far as African religious practices were concerned, these were deemed non-existent: the Code noir regards them as supposedly ‘seditious’ practices, and as a result, any gathering of slaves was strictly forbidden.

It is important to emphasise the exceptionally harsh working conditions endured by slaves on plantations and in homesteads. Slavery resulted in an increase in wealth for France in Saint-Domingue, but also for the whole of Europe which, between the sixteenth to the nineteenth century, deported between twelve and fifteen million African slaves for the production of sugar cane, cotton, coffee, indigo, and cocoa (see, for example, the demographic data in Coquery-Vidrovitch and Mesnard 2013, 122). In Saint Domingue, slaves worked from morning until night under the strict supervision of slave masters armed with whips. In theory, masters resorted to a strategy which prevented slaves from finding themselves reunited with other members of the same ethnic group, since it was considered essential to use any possible means to ensure slaves were kept in a situation of total subjugation to the power of their masters. In practical terms, a slave was considered to have neither ancestors nor descendants. This is why certain sociologists speak, with good reason, of ‘social death’ to describe the total depersonalisation masters sought to impose on their slaves (Patterson 1982). These working conditions, similar to those within a concentration camp, would end up driving the slaves to look for ways to restore their lost identity, by weaving a new social fabric which would unite them in the struggle for liberation.

The cult of the dead in the development of Vodou

For the slaves, the cult of the dead was not only a link to African religious and cultural traditions. It also represented the foundation of new practices and perceptions which the slaves would introduce in their own way, as a result of the subjugation imposed on them by the institution of slavery. The cult of the dead was not just an African heritage but was also overlaid with a new significance. If the slave trade is a process of deportation that tore the individual away from his or her family, lineage, and clan, it is only to be expected that when a slave dies, every possible step must be taken in order to enable the restoration of links with the native land. Slave funerals in the colony involved rituals which were designed to re-establish contact between the dead slave and his or her ancestors. Such rituals sought out the divinities responsible for protecting lineage and ethnic groups. The religious and cultural heritage of Africa was gradually restored through this semantic chain, which represented the link between the dead person and his or her ancestors and their divinities. Many commentators and historians point out that the slaves believed they would return to Africa after their death and sometimes those who took their own lives expressed their hope of returning home by doing so.

In addition to burial, two other significant moments in the development of Vodou stand out. Slaves were allocated Sunday evenings as leisure time and these evenings provided them with the opportunity to organise dances, known as calendas. These dances enabled the slaves to revisit some of their African traditions, far from the gaze of the slave masters. The second key moment is what is referred to as marronage (Fouchard [1972] 1988): the process by which slaves fled into remote mountain regions where they were sometimes able to meet up with members of their ethnic groups but, in any case, could organise a life of freedom. Marronage has been the subject of a great many studies and is recognised as the expression of the desire for freedom and, therefore, as an unmistakable expression of protest against the condition of slavery (see for example Fouchard 1962 and Fick 2017).

The plantation masters in Saint-Domingue greatly feared marronage, and imposed severe punishments for it. But they had enormous difficulty finding out what was being plotted in the cultural and religious practices of the slaves, given that the latter demonstrated, for example, a sincere devotion to prayers, mass, and the worship of saints and of the Virgin Mary in churches and were eager to take part in religious processions. Chromolithographs representing the saints decorated the Catholic churches that the slaves were obliged to attend. These images provided the slaves with details that enabled them to keep depictions of African divinities alive. Hence the syncretism which, at first sight, still marks out Haitian Vodou, as it does Brazilian Candomblé and Cuban Santeria.

Vodou and the slave rebellion of 1791

From the beginning of the second half of the eighteenth century onwards, many religious readers from both Catholic churches and from marronage communities began calling for revolt, drawing on the support of large numbers of slaves. These leaders included Padre Jean who, in 1786, gave his name to a Vodou ritual known as Petro, and Colas Jambes Coupées, a maroon (i.e. a former slave who lived in freedom) who was regarded as a sorcerer and who encouraged slaves to abolish the colony. Of great importance was the famous Makandal who, as early as 1751, had prophesied the death of whites and the end of slavery. Makandal was suspected of being a specialist in recipes for poisons and magic potions and his name remains associated with the witchcraft practices and beliefs called makanda. Arrested and sentenced to be burnt alive, it was said throughout the colony that Makandal managed to escape the flames by transforming himself into a lizard. Recent research refers to a ‘Makandal site’ (Midy 2003) associated with the Haitian revolution, since it was from the settlement named Normand LeMézy in the north of the country where he operated that the idea of a general slave revolt gradually began to spread. It is important to focus our attention on this key event in the history of Vodou, which will always be linked to the process of the anti-slavery revolution which in turn gave birth to the Haitian nation (see Fick 2014).

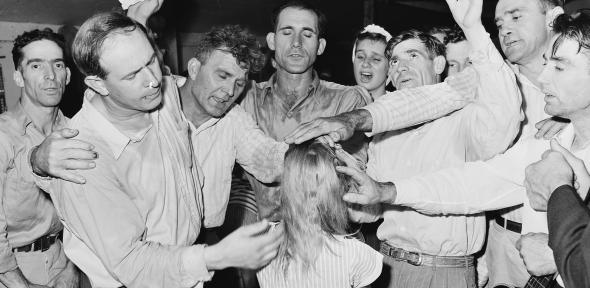

On the 14th of August 1791 near Morne-Rouge, in a place called Bois-Caïman, around 200 slaves, commanders, coachmen, domestic slaves, and representatives of various sugar production workshops gathered for a Vodou ceremony organised under the leadership of Dutty Boukmann, a slave in a plantation in the north-east of the country and a Vodou priest (houngan). According to early accounts, available thanks to the writings of surgeon Antoine Dalmas who was present at the ceremony (1814), the participants sacrificed a pig to African divinities and swore to bring slavery to an end and to launch a general insurrection. They drank the blood of the sacrificed animal and pledged to keep the future rebellion a secret. Also officiating at the ceremony was a woman by the name of Cécile Fatima. Certain historians (Geggus 2002) provide a dramatised version of the ceremony, describing it as taking place during a stormy night. One week later, in the night of the 22nd to 23rd of August, the revolt broke out: all the sugar and coffee plantations, along with the workshops of Saint-Domingue, were burnt down over a wide area. Catholics were also involved in this revolution. They include a maroon known as Romaine the Prophetess who declared herself to be the goddaughter of the Virgin Mary from whom she received messages telling her to free 4000 blacks and mulattos from slavery.

The outcome of the rebellion was disastrous for the colony, with many hundreds (perhaps even as many as a thousand) colonisers being killed, and 1,200 coffee plantations and 161 sugar plantations destroyed by fire. The French government estimated the losses at 600 million pounds (Cauna 1987, 212).

Saint-Domingue at this date was a powder keg, with 500,000 slaves—many of whom had escaped and were living as maroons in camps in the mountains. There were also 40,000 emancipated mulattos and blacks and 30,000 whites, the latter divided into ‘poor whites’ (petits blancs: craftsmen, traders/merchants, sailors, and soldiers) and ‘the white elite’ (grands blancs: planters and administrators). The Code noir of 1685 had for decades controlled relationships between these groups on the basis of a strict racial hierarchy which went from whites, through mulattos, to blacks. As soon as news of the French revolution arrived in Saint-Domingue, all social and racial groups were galvanised into action. Nine years after the Haitian revolution, in 1882, Napoleon attempted to reinstate slavery. His attempts to do so led to a war in Haiti, with 40,000 men sent out from France, that ended with Haiti’s independence. It is highly likely that secret Vodou societies were involved in this war.

Having established the historic roots and the historical importance of Vodou, we now turn our attention to the pantheon of this religion and the rituals associated with it. We shall then examine how anthropology accounts for this system of beliefs and practices.

The Vodou pantheon and its rituals

In Africa (notably in Benin and Nigeria), three types of Vodou can be identified: one associated with family or lineage (hennu-vodu), one with the village (to-vodu), and one with ethnic groups (ado-vodo). The divinities are divided into celestial groups (Mawu-Lisa being responsible for day and night, while Gu is in charge of organising the universe); then in terrestrial groups (wih Agwe or Agbe for the sea and the waters, or Sogbo for the rain) and finally in groups of divinities representing the storm (such as Ogou-Badagri, master of the thunder). In the case of Saint-Domingue/Haiti, the African divinities (called lwa, spirit, or mistè) are divided into the rada divinities (representing the Fon and the Yoruba people) and the Congo and Petro divinities (for the Bantu and Creole people, respectively). They represent a transformation of ethnic groups into families of divinities (called nanchon, or nations) and constitute a genuine pantheon. God is recognised as the ‘great master’ (Granmet) who leaves to the lwa, the secondary divinities, the task of dealing with earthly matters. Divinities therefore mediate between humans and their world. They represent an imaginary and symbolic field that serves as the foundation of social relations, and enables the mutual recognition between slaves and their solidarity during revolts.

The value of one lwa in the pantheon is a little like that of a word in a language: its value changes and can only be understood in a relationship of contradiction and of complementarity with the other lwa, and therefore with the entire family of divinities. So, for example, Legba, the ‘leader’ of the lwa, opens the gate separating humans from the world of the lwa. Represented by Saint Peter, he is also the guardian of temples (called ounfor) and of dwellings, and is invoked at the beginning of each Vodou ceremony. Legba is also ‘master of the crossroads’, places that are associated with danger but that are also home to objects known as wanga, which can protect against evil spirits and allow their owners to bewitch others. Amongst the important lwa is also Ogou, represented by Saint James the Great, as a warrior. His favourite colour is red and he is associated with fire, but he stays in contact with water where he is reunited with the lwa Ezili, the flirtatious and sensuous woman represented by the Virgin Mary, who is his mistress. Ogou is also the cousin of Zaka, lwa of agriculture, whose adoptive son is Brave Gédé, spirit of the dead and of cemeteries. Many of these lwa are associated with the Rada subsection of Vodou, but in Congo and Petro subsections of Vodou these spirits can also be present. So, for example, the Lwa rada, known as the twins (or marassas), are reputed to be fearsome (Heusch 2000).

The Vodou temples (ounfor)

The lwa are regularly honoured in ounfor, which are the Vodou temples where ceremonies take place. It would appear that ounfor were built all over Haiti after independence in 1804. In charge of the ounfor is an ounfan, who is the owner of the temple. A woman priest can also be the owner of an ounfor and is called a manbo. At the entrance of an ounfor there is often a tree, the calabash, which is the residence of lwa Legba.

The decorations of the ounfor, which consist of images of Catholic saints, might seem misleading as in reality these represent the lwa most often honoured there. Such images are housed in chambers (kay-mistè) in which are placed their favourite foods and their symbolic objects, mostly during ceremonies. The lwa Ezili, who is represented by a flirtatious woman, will, for example, receive a mirror. The ceremonies, which consist of dances and songs in honour of the lwa, take place in a large room called the péristil. In the middle of the péristil, acting as a connecting link between the earthly and the celestial worlds, stands a pillar called the poto-mitan, often decorated with two snakes (Dambala-Wedo and his wife, Ayida Wedo, joined together like fire and water). Divinities from mythical Africa pass through the poto-mitan after an epic journey under the waters of the Atlantic to be reunited with their servants in the temple. Around the poto-mitan stand the oungan or the manbo, the ‘chanterelle queen’ who directs the dances and songs, the initiated or ounsi ready to sing and to dance, and the other participants (pitit kay) who are welcomed as members of the fraternity (see below). Opposite them is an orchestra composed of three drums which are used as sacred instruments and play the tunes associated with the lwa in order to facilitate trances and possession. At the start of each ceremony, geometric patterns (vèvès) representing the lwa are drawn on the floor with coffee or flour, and these help to incite states of trance. Emblems of the lwas are placed on a table resembling an altar: food dishes and various objects such as bottles containing the souls of the dead placed under the protection of the lwa.

The major places of Vodou worship in Haiti include the temples of Souvenance and Soukri, both close to the port-city of Gonaïves. Each year, at Easter and in August, thousands of visitors and practitioners, including the Haitian diaspora, gather there to celebrate. In fact, throughout the year, celebrations marking the patron saints also attract Vodou practitioners who readily transform these into occasions of Vodou pilgrimage. For example, on the 16th of July, the feast of the Saut d’Eau, dedicated to Our Lady of Mount Carmel, attracts many tens of thousands of pilgrims to a famous waterfall surrounded by trees believed to house Vodou divinities. Often the pilgrims also attend the local church, and display the same levels of enthusiasm and devotion as at the site of the famous waterfall.

What is the nature of the lwa, and what are their demands? In themselves they are neither good nor bad since their impact on our lives depends on how we follow their rules. Together, the lwa are part of a hierarchical system, and those who take precedence over others need to be honoured more lavishly.

Honouring the lwa (Vodou rituals)

How should the lwa be honoured, and what do they represent today in people’s individual and collective lives? An individual generally receives one or two lwa as part of his or her family heritage. These are referred to as the lwa-rasin, or ‘root-lwa’: some Haitian families have, tucked away somewhere out of sight in their room, a small alter called wogatwa on which is placed the image of a saint which is indeed the inherited lwa who they worship on a regular basis. On a collective level, there are fraternities to which individuals belong within an ounfor. People attend or actively participate in ceremonies which follow the Catholic liturgical calendar. On Christmas night, they ask for favours of the lwa; on the 6th of January, the Feast of Kings is the occasion for a ceremony bringing together a number of families, and on the 1st and 2nd of November, the festival of the dead gives rise to festivities worthy of a national holiday which take place in cemeteries (Metraux 1958, 216ss). Throughout the year, oungan and manbo are consulted and act as official interpreters for the language of the Vodou divinities in order to guide individuals in their daily lives.

To obtain the favours of the lwa, offerings must be made to them on a regular basis. These can involve pouring water on to the ground (jétédlo) in order to give the lwa a drink, an opening gesture in ceremonies. Animals (poultry, goats, or bulls) are sacrificed in order to provide food for the lwa (manger-lwa). Of course, each ritual must be strictly applied so as to avoid the risk of provoking the anger of the ‘spirits’. A ceremony generally culminates in one or more participants becoming possessed, a phenomenon which, for Vodou practitioners, means taking the form of a lwa, allowing oneself to be possessed by it (a process described as ‘overlapping’ with the lwa), by falling into a trance. At the first signs of such a trance, the Vodou practitioners present prepare to welcome the lwa and offer the objects and symbols associated with that lwa. Such an epiphany of a lwa is sign of a successful ceremony.

Certain Vodou practitioners go further than the traditional relationships they have with the lwa in the context of their family or fraternity. They may have a deeper relationship with a particular lwa. Normally it is the lwa who is believed to select the individual in question. In this way, a ‘mystical marriage’ with a lwa can take place, either as a result of a dream, an illness, an accident, or repeated failures in matters of everyday life. This ceremony takes the form of an ordinary marriage with a blessing of rings in the presence of witnesses. The lwa gives his or her agreement to the marriage through a dream or by taking possession of the mind of a participant. These mystical marriages are a way of transmitting the legacy of lwa since it is thanks to a godfather (or a godmother) who has already experienced an initiation that this transmission can take place, the newly married individual then becoming a godchild. He or she must set aside certain days of the week to make offerings to the lwa and must accept sexual abstinence.

Sometimes certain Vodou practitioners seek to buy lwa whom they have not inherited from an oungan or a boko, in order to acquire additional protection or to cast spells on potential enemies. There are, however, risks associated with this, since a lwa can in return make demands which are difficult to honour.

Initiation is a ritual which takes place after several days (or weeks) of seclusion in an ounfor. The individual who has been chosen by a lwa cannot easily escape that fate. But he or she can choose to become an initiated person (ounsi) which means being able to live the rest of his life with the lwa attached to his head like a permanent protection. The initiation period corresponds in fact to the time needed for the individual to become familiar with the customs of the lwa, the healing leaves and plants, the dishes; in short, all the objects linked to this particular lwa. A solemn ceremony marks the moment when the initiated person emerges, accompanied by their godfather and godmother. When they die, the initiated must undergo a ritual of separation (desounen) from the lwa, to allow him or her to peacefully depart from the world of the living. A long initiation period is also required for a Vodou priest to become an official interpreter of the lwa, a role usually passed down through families. Vodou secret societies can also be included in the context of initiation practises. These societies are part of the West African heritage and are referred to by names such as Chanpwel, Zobop, and Bizango, and they meet only at night. They operate under a strict hierarchy under the command of an oungan who takes the title of emperor. The aim of these societies is to defend Vodou and its temples, and they are often suspected of deploying the powers of witchcraft. As a result, they are regarded with fear. This association with witchcraft is widely used in Protestant preaching to convert Haitians from the lower classes to charismatic Protestantism (Hurbon 2001).

Advances in anthropology

Amongst the issues which have captured the attention of Vodou anthropology are the phenomena of possession, witchcraft, and syncretism. Possession was, until recently, thought to be associated with hysteria or a pathological phenomenon linked to psychiatry. This interpretation was based on the notion that convulsions or the loss of self-control were considered abnormal. It was not until the work undertaken by Claude Lévi-Strauss following Marcel Mauss, and inspired by new research in linguistics in the 1950s, that possession would come to be seen as a form of language. Moments of possession in a Vodou ceremony were seen as perfectly normal by members of the audience. Nobody would be upset by it, since what is normal must be understood according to the roles of the existing cultural system. By following this route of symbolic analysis opened by Lévi-Strauss, an explanation of the relationship of individuals and of society to the Vodou divinities could finally be established (see Hurbon 1972, 1987). During the process of possession, the lwa must recieve special greetings, particular drum rhythms and dance steps which enable he or she to be identified, and symbolic objects, such as a sword in the case of Ogou, the lwa of war. The actions of recognition of divinities in the form of ceremonies and rituals constitute a language, and enable the individual to recognise his or her place in society. By following these rituals, the Haitians affirm their identity, recall their painful and unique history, and acknowledge that they have access to the powers of the lwa to help them deal with the difficulties life holds. For losing the language of the lwa means putting yourself under the control of a dual relationship of self to self and quite simply losing language altogether. The lwa take charge of the individual’s life and place it in a field of meaning by classifying the different domains of social life and of nature in such a way that all events, happy or sad, find a meaning.

At the same time, possession implies a permanent fragility of the body which needs to be protected against the intrusion of bad spirits or of spells cast on the individual in question. Possession is never left to run its own course but must be to some extent coded, controlled, and mastered. Magic and witchcraft are, as a general rule, frowned upon by Vodou practitioners. They represent a negative and dangerous side of Vodou from which individuals should distance themselves as far as possible (Heusch 2000). But, based on the principle that the body of an individual can be penetrated or possessed by spiritual forces (in the form of the lwa or by the ‘spirits’ of the dead), an enemy can inflict on that same individual negative forces capable of causing sickness or even death. Initiation and mystical marriage exist precisely in order to strengthen the protection of Vodou practitioners. Nevertheless, it is important to acknowledge the famous distinction made by the anthropologist E.E. Evans-Pritchard (1972) between witchcraft and sorcery: witchcraft can be understood as a technique made up of ritual gestures, physical objects, and knowledge or gifts to the service of an individual, whereas sorcery is a power attributed to people supposedly capable of taking possession of an individual’s vital substance against his or her will.

The other important step in the anthropology of Vodou is the one achieved as a result of Roger Bastide’s work on syncretism. This blend of elements of the Catholic religion (prayers, images of saints, enthusiasm for baptism) and of purely African traditions (divinities or spirits dwelling in trees or in the water, and capable of taking over the body through possession) is easily misinterpreted. Indeed Bastide (1967) demonstrates for the first time that the cultural elements observed in Vodou are not simply juxtaposed: he applies the ‘compartmentalization principle’ in order to demonstrate that the black communities formed as a result of slavery easily passed from one religious system to another, without turning it into one single system. This ‘compartmentalization principle’ allows us to understand the capacity to use any one cultural element as a mask or a screen to help preserve an individual’s own African heritage, and at the same time as a way of reinterpreting this heritage on the basis of elements borrowed from the other system, and vice-versa. We are then confronted with a process of cultural creativity in which heterogeneous and hybrid elements can coexist.

Another interesting area of anthropological research focuses on the significance of the masculine and feminine in Vodou religions. Lidwina Meyer (1999) demonstrates that in the texts of Vodou myths, there is a gradual gender difference that exists which moves from masculine to feminine by means of a play of masks and of various roles relating to sexuality. This makes it possible to move away from the traditional opposition between feminine/masculine, mind/body, and self-identity /non-self. This analysis leads us to challenge the inferiorisation of women and the arbitrary place given to man as supposedly ‘universal’. It is indeed striking that few normative discriminations in terms of gender seem to exist in Vodou. Women can be priestesses and can take on all sorts of roles in an ounfor.

Misconception

During the first half of the nineteenth century, Vodou was merely tolerated by the first Haitian state leaders who were reluctant to acknowledge it as a religion at a time when Catholicism was the official religion recognised by the state. The country’s elites were aware of the subversive role Vodou had played during the revolution, and knew that it could potentially reveal the presence of powers parallel to those of the state. Nevertheless, Vodou remained firmly attached to the Catholic Church, functioning almost in osmosis with it. Moreover, since the 1820s, the Haitian government had embarked on various attempts to negotiate with the Vatican for the official recognition of Haitian independence, and it was only in 1860 that a concordat was signed between the Haitian government and the Vatican. From that date onwards, Haiti welcomed missionaries from Brittany to engage in public teaching and establish Catholic parishes throughout the whole country (see Delisle 2003). A new ‘civilising’ vision would be offered to the country by the Catholic clergy, and Vodou was portrayed as a hotbed of magic practices, witchcraft, and cannibalism. These were the prejudices already in circulation with regards to African practices and beliefs. According to the Catholic missionaries, Haiti should rid itself of what was referred to as its ‘African flaws’ represented by Vodou, in order to put itself on the same level as the ‘civilised’ nations. The interpretation of Vodou based on the contrast between the ‘barbarian’ and the ‘civilised’, which has long dominated the country, stems first of all from the perception of the missionaries and administrators of the colonial period, and then that of European visitors in the nineteenth century (like St John 1884).

Take, for example, this extract from a speech made by a French bishop, Francois Marie Kersuzan, in 1896:

This is our chief enemy, the one we must fight ceaselessly against, a fight to the death. Let us look at it face to face, in order to see it in its full horror and to enable us to conquer it successfully. Many people think that Vodou amounts to obscene dances and copious feast. Vodou is true devil worship with its sacrifices and its pontiffs and the dances are only the crude exterior of a hellish interior.

Such misconceptions are consistent with the colonisation movement based on a European project to ‘civilise’, which flourished during the nineteenth century. Anthropology, emerging at the end of the eighteenth century and in the nineteenth century initially supported this project insofar as it ‘ordered the diversity of races and of peoples, and gave them a rank, that is to say a role in history’ (Duchet 1971); in this instance, the role of the ‘savage’. From this perspective, the theory of a supposedly ‘scientific’ racism was formulated at the end of the nineteenth century.

In the immediate aftermath of this urge to ‘civilise’, Vodou would be subjected to two major waves of persecution by the Catholic Church, which had become the official state religion in 1860. In the first of these, in 1896, the church urged the Catholic faithful to explicitly reject Vodou practices and beliefs. Then in 1941, it launched a major national campaign with auto-da-fe, known as the ‘anti-superstition campaign’ (la campagne de ‘rejeté’) which insisted that each parishioner take an oath renouncing Vodou as a renunciation of ‘Satan and all his works’ (see Metraux 1958, 298ss; Ramsey 2011). This campaign was strongly criticised in 1942 by the ethnologist and writer Jacques Roumain, founder of the National Bureau of Haitian Ethnology, dedicated to collecting and protecting sacred objects associated with Vodou and to promoting research on all aspects of Vodou and on the cultural traditions of the country.

The surge of intellectuals: Vodou as a site of memory

The American occupation of Haiti from 1915 to 1934 would also provoke a resurgence of the pejorative view of this religion. At the same time, there was a surge in numbers of Haitian intellectuals with, for example, Jean Price-Mars publishing in 1928 a collection of essays titled Ainsi parla l’oncle (translated in 1954 as So spoke the uncle) in which he sought recognition for the African origins of Haitian culture and therefore for Vodou as a religion which Haitians had the right to call their own. Important publications (for example Métraux 1958; Verger 1957) introduced ethnographies of Vodou that acknowledged its role in the restoration of dignity to Africans deported into slavery, and its status as an original cultural creation as a testimony of their identity.

After the explicit attempts at political manipulation of Vodou during the thirty years of the Duvaliers’ dictatorship, Francois Duvalier declared himself to be its defender. Yet he did exploit it by making certain oungan his representatives in the towns and countryside (see Hurbon 1979). Today, the religion continues to suffer the effects of the huge wave of new Pentecostal churches. As a result of their preachings, these churches provoke a resurgence of the idea that witchcraft is very much the prerogative of Vodou. At the same time, Vodou maintains a horizontal position across the various religious systems competing within the country, in the sense that Vodou practitioners see no difficulty in declaring themselves Catholic and in accepting baptism and communion in church. In the same way, whereas the lwa are demonised in Pentecostal Protestantism, this nevertheless shares some beliefs pertaining to dreams and to trances of the holy spirit which are also found in Vodou.

With the process of democratisation that the country experienced after the end of the dictatorship in 1986, a number of Vodou priests were lynched for reputedly actively supporting the dictatorship. Since that time, Vodou has managed to create its own organisation in defence against the vandalism and intolerance of some religious denominations.

At the same time, Vodou seeks to obtain the same privileges as other religions, such as, for example, the right to officially celebrate baptisms, marriages, and funerals. Even today, political leaders still evoke the ‘mystical powers’ of Vodou in their speeches in order to gain legitimacy with the working classes. But, ultimately, the various art forms inspired by Vodou, such as painting, sculpture, music, dance or literature, have enabled it to gain recognition as one of the sites of Haitian individual and collective identity (Consentino 1995). Modern anthropology should set itself the task of exploring these links, and in doing so it will discover that Vodou is a place of memory not only for the Haitian nation but also for humanity at large. It did, after all, witness the struggles endured by the slaves for the recovery and recognition of their human dignity.

Conclusion

Vodou has inspired some important research into its relationship with naive painting, a relationship described by Andre Malraux in 1975 as ‘the most striking experiment in magical painting in our century’. Yet many Haitian artists often choose the route of ‘sophisticated’ painting while at the same time acknowledging the inspiration of Vodou (see the latest work of the art historian Philippe Lerebours [2018] and the sumptuous work of Gerald Alexis [2000]). Vodou should also be inventoried on a scientific basis with reference to its various therapeutic resources for the body and mind thanks to its knowledge of plants and their medicinal value. Several exhibitions of Haitian painting have taken place in France, in Switzerland, and in the United States, but where other cultural categories are concerned, anthropology should see new breakthroughs. Vodou undoubtedly remains a living culture that owes its richness to the integration of various influences, thanks to the scale of the Haitian diaspora (in the US, Canada, the Caribbean, and Latin America), which continues to turn to the beliefs and practices of Vodou.

Questions arise as to the role played by Vodou in the Haitian revolution, the ambivalent attitudes of Haitian governments from independence in 1804 to the present day, and on the secret societies which still exert a powerful influence on the imagination of working-class Haitians. Important research also remains to be undertaken on the sacred objects of Vodou and on the places associated with its resistance to slavery which are now memorial sites: they can improve our understanding of the influence that the Haitian Revolution has had on present-day fights against racism.

Glossary

Boko: name given to Vodou priests (oungan) capable of providing offensive or defensive magic practices

Désounen: a ritual of dispossession conducted on an initiate in order to separate them from the spirit he or she was attached to

Lwa: spirit or secondary divinity

Lwa mèt-tèt: protective spirit received during initiation which ensures a lwa is attached to an individual in order to protect that person until their death

Lwa-rasin: a spirit passed down through the family

Manbo: Vodou priestess

Manje-lwa: ceremony during which dances and offerings (food and animal sacrifices of chicken, beef, or goats) are made in honour of Vodou divinities, under the supervision of an oungan or manbo

Ounfor: Vodou temple

Oungan: Vodou priest

Ounsi: Vodou initiate

Pedji: special room reserved for lwa

Péristil: space where Vodou ceremonies take place

Poto-mitan: pillar in the centre of the péristil through which spirits can travel to the human world

Pwen: supernatural power or protective force

Vèvè: symbolic drawing, referring to a lwa

Wanga: ordinary magic weapon

References

Alexis, G. 2000. Peintres haïtiens. Paris : Edition du Cercle d’Art.

Bastide, R. 1967. Les Amériques noires. Paris : Payot.

Cauna, J. 1987. Au temps des isles à sucre. Paris : Editions Karthala.

Consentino, D. 1995. Sacred arts of Haitian Vodou. Los Angeles : University of California Los Angeles Fowler Museum of Cultural History.

Coquery-Vidrovitch, C. & E. Mesnard 2013. Etre esclave : Afrique-Amériques, XVe-XIXe siècle. Paris : La Découverte.

Dalmas, A. 1814. Histoire de la révolution de Saint-Domingue. Paris : Mame Frères.

Delisle, Ph.. 2003. Le catholicisme en Haïti au XIXe siècle : le rêve d’une «Bretagne noire». Paris : Karthala.

Desquiron, L. 1990. Les racines historiques du vodou. Port-au-Prince : Editions Deschamps.

Duchet, M. 1971. Anthropologie et histoire au siècle des Lumières. Paris : Maspero.

Dutertre, J.B. 1666. Histoire des Antilles habitées par les Français, t. 1-III. Paris : Jolly.

Evans-Pritchard, E.E. 1972. Sorcellerie, oracle et magie chez les Azandé. Paris : Gallimard.

Fick, C. 2014. Haïti, naissance d’une nation : La Révolution de Saint-Domingue vue d’en bas (trad. de l’anglais par F. Voltaire). Montréal : Les éditions CIDHICA.

Fouchard, J. 1988 [1972]. Les marrons de la liberté. Port-au-Prince : Editions Henri Deschamps.

Geggus, D. 2002. Haitian revolutionary studies. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Garrisson, L. 1998. L’Edit de Nantes, Paris : Editions Fayard.

de Heusch, L. 2000. Kongo en Haïti. Dans Le roi de Kongo et les monstres sacrés. Paris : Gallimard.

Hurbon, L. 1979.Culture et dictature en Haïti : l’imaginaire sous contrôle. Paris : Editions L’Harmattan.

——— 1987 [1972]. Dieu dans le vaudou haïtien. Paris : Payot et Port-au-Prince : Éditions Henri Deschamps.

Kersuzan, F.M. 1896. Conférence populaire sur le vaudoux donnée le 02 août 1896. Port-au-Prince : Imprimerie H. Amblard.

Justinvil, F. 2020. Sociétés secrètes en Haïti. De l’imaginaire au réel. Port-au-Prince: livre électronique.

Lacan, J. Ecrits. Paris: Éditions du Seuil.

Lerebours, M. Ph. 2018. Bref regard sur deux siècles de peinture haïtiennes. Port-au-Prince: Edition de l’Université d’Etat d’Haïti.

Lévi-Strauss, C. 1958. Anthropologie structurale. Paris : Plon.

Métraux, A. 1958. Le vaudou haïtien. Paris : Éditions Gallimard.

Meyer, L. 1999. Das fingierte Geschlecht. lnszenierungen des Weiblichen und Mannlichen in den kulturellen Texten des Oriha-und Vodun-Kulte am Golf von Benin. Frankfurt am Main : Peter Lang.

Midy, F. 2003. «Vers l’indépendance des colonies à esclaves d’Amérique : l’exception haïtienne.» Dans Haïti première république noire (ed.) M. Dorigny, 121-38. Paris : Publication de la société française d’histoire d’outre-mer et association pour l’étude de la colonisation européenne.

Moreau de Saint-Méry, M.L.E. 1958 [1797]. Description topographique, physique…. De la partie française de l’isle de Saint-Domingue. Paris: Société de l’histoire des colonies françaises.

Patterson, O. 1982. Slavery and social death: a comparative study. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Price-Mars, J. 1928. Ainsi parla l'oncle. Compiègne : Bibliothèque haïtienne.

Ramsey, K, 2011. Vodou and power in Haiti: the spirits and the law. Chicago: University Press.

Roumain, J. 1942. A propos de la campagne antisuperstitieuse. Port-au-Prince : Imprimerie de l’Etat.

Sala-Molins, L. 1987. Le Code noir ou le calvaire de Canaan. Paris : Presses universitaires de France.

St John, S. 1886 [1884]. Haïti ou la république noire. (trad. J. West) Paris : Plon.

Verger, P. 1957.Notes sur le culte des orisha et vodoun à Bahia… et l’ancienne Côte des esclaves en Afrique. Dakar: IFAN.

Note on contributor

Laënnec Hurbon obtained a PhD at Sorbonne University and is Research Director of the French National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS). He is also a professor at the State University of Haiti and specialises in studying the relations between religion, culture and politics in Haiti and the Caribbean. He is the author of various works, including Les mystères du vaudou, published with Gallimard, and Le barbare imaginaire, published with Editions du Cerf.

Note on translation

This text has been translated by Helen Morrison from: Hurbon, L. 2021.Vodou Haïtien. In The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Anthropology, edited by Felix Stein. Online: http://doi.org/10.29164/21vodouhaitien.

Helen Morrison, BA in Comparative Literature and French and M.Phil on Dadaist littérature, University of East Anglia, is a freelance translator (French to English) and has translated eight books for Polity Press.