Animism is a particular sensibility and way of relating to various beings in the world. It involves attributing sentience to other beings that may include persons, animals, plants, spirits, the environment, or even items of technology, such as cars, robots, or computers. Through ethnographic examples drawn from animistic societies worldwide, this entry examines key themes in the study of animism, from principles of animation to attributing sentience to animal spirits and animistic places. Since early and contemporary anthropological approaches to animism are often grounded in the principles, philosophies, and conclusions of modern science, anthropologists use a variety of concepts such as immanence, transcendence, or disenchantment to understand animistic sensibilities. By contrast, animistic persons do not rely upon the concepts of scholars to understand their own worlds. Recently, anthropologists have approached animism as a particular ‘ontology’ in the world, bringing it into conversation with related ontologies such as totemism, analogism, naturalism, and a newly proposed homologism. These and other terms are briefly explained while humour and reflexive awareness are explored as themes that push anthropologists to re-envision the effects of imagination and creativity in a variety of animistic worlds.

Introduction

Animism is both a concept and a way of relating to the world. The person or social group with an ‘animistic’ sensibility attributes sentience – or the quality of being ‘animated’ – to a wide range of beings in the world, such as the environment, other persons, animals, plants, spirits, and forces of nature like the ocean, winds, sun, or moon. Some animistic persons or social groups furthermore attribute sentience to things like stones, metals, and minerals or items of technology, such as cars, robots, or computers. Principles of animation and questions of being are thus key to animism. That said, animism is best understood not only in terms of what it is, but in terms of what it is not. At first glance, animism seems to conjure up a coherent and deliberate ideology of sorts, as it ends in an ‘ism’. But animism is really more a sensibility, tendency, or style of engaging with the world and the beings or things that populate it. It is not a form of materialism, which posits that only matter, materials, and movement exist. Nor is animism a form of monotheism, which posits a single god in the universe. And, it is not a form of polytheism that posits many gods.

Instead, to an animistic person or social group, sentience is often envisioned as a vital force, life force, or animated property that is ‘immanent’, accessible, and ‘ready to hand’ in the everyday world, even if this property is usually latent and not perceivable. There is often an important contrast between the ‘immanence’ of animistic sensibilities and the ‘transcendent’ qualities attributed to a monotheistic god or polytheistic gods, which are related to as beings that exist apart from the everyday lives of human beings.

Just what it is that animates any particular being or thing can vary between different animistic persons and societies. Urban shamans in Stockholm tend to approach the world with an animistic sensibility that is rather different to that of Lutheran Swedes, when they consider that ‘everything is alive and permeated with “Spirit”’ in a world comprised of both the “ordinary”, physical reality we live in [… and] another, “alternative” reality, inhabited by living forms or energies sometimes seen as “Spirits”’ (Lindquist 1997: 13). Yet another kind of animistic sensibility is found among the indigenous Siberian hunters known as Yukaghir, who ‘differentiate between conscious and unconscious beings’ (Willerslev 2007: 73). As the anthropologist Rane Willerslev observes, ‘[a]n elderly Yukaghir hunter, Vasili Shalugin, told me that animals, trees, and rivers are “people like us” (Rus. lyudi kak my) because they move, grow, and breathe, but they are distinct from inanimate objects such as stones, skis, and food products, which, he claimed, are alive but immovable’ (2007: 73). Some Yukaghir further consider that static things are not people because they only have one soul (known as the ‘shadow-ayibii’), while active things are considered to be people since they have additional souls, which make them move and grow (the ‘heart-ayibii’) as well as breathe (the ‘head-ayibii’) for example (Willerslev 2007: 73).

These two ethnographic studies point to seminal themes in the study of animism. One theme is the existence of various kinds of ‘spirits’ and ‘souls’. Spirits are understood in a broad sense that encompasses the spirits of beings or things, deities, and energies. Souls are often the spirits of beings and things, depending on the social context. There is no set definition for animism, just as there is no set definition for spirits or souls. Yet a general feel for how the terms animism, spirits, and souls are understood can be gleaned from the ways that scholars (and, in some cases, animistic persons) apply them to social contexts. Urban Swedish shamans and Siberian Yukaghirs, for example, hold in common the animistic logic of immanence. Animistic sensibilities may appear at any moment and thus pervade the societies of Swedish urban shamans and Yukaghirs alike.

A second theme in the study of animism revolves around the attribution of personhood. For the Yukaghir, active things like animals, trees, and rivers are ‘people like us’ because, like human beings, they possess certain kinds of souls. It is these shared souls that imbue animals, trees, and rivers with a sentience that enables them like humans to move, grow, and breathe. By contrast, static things like stones, skis, and food products are ‘not persons’ because they only share one soul in common with humans and lack the kind of sentience that would enable them to move and show signs of animated life, consciousness, and motivation. Not all beings or things have the same animistic sensibilities in the Yukaghir ‘life-world’, which is quite literally a world that is largely alive to sentience. Yet – and this might perhaps go against the reader’s expectations – we find a more comprehensive case of animistic immanence in the life-world of urban Swedish shamans, who relate to ‘everything’ like a living person who is filled with Spirit.

Given this difference in animistic sensibilities, the following questions arise: Is there an archetypal form of animism in which spirits or souls animate all beings, as is the case among urban Swedish shamans? If so, could this form have undergone a process of ‘diminution’ or ‘disenchantment’ in some societies, which caused certain of their animistic sensibilities to become less important or widespread? Would disenchantment explain why Yukaghir view their stones, skis, or food products as being ‘not people’? Conversely, have Swedish urban shamans sought to inhabit a ‘re-enchanted’ world, where everything has Spirit?

Note that while these terms and questions need to be explained by scholars of animism, they do not need to be explained to animistic persons who already relate to the world with animistic sensibilities. Yukaghirs would not need to use scholarly terms such as immanence, life-world, disenchantment, or diminution in order to understand how an animistic sensibility works. They already inhabit a life-world in which there are clear relationships between souls, beings and things – relationships that separate ‘people like us’ from those that are ‘not people’.

Anthropologists, ethnologists, ethnographers, folklorists, religious studies experts, and popular experts alike have grappled with the aforementioned specialist terms when reflecting upon the multitude of animistic societies, both in the contemporary world and historically. It is thus important to note the sometimes subtle but key difference between the persons who live animistic lives and those who study animistic persons but are not necessarily animistic themselves. Revealing discrepancies often arise between the animistic sensibilities of the persons of study and the sensibilities of scholars. This is particularly obvious among anthropologists, who have been leading figures in the study of animism. Both early and contemporary anthropologists often approach animism in an ‘as-if’ manner that suggests they themselves do not relate to the world in an animistic way. Nonetheless, many current anthropological works on animism are subsumed under what Graham Harvey, in a neo-pagan and eco-friendly vein, dubs the ‘new animism’ (2017 [2005]: xvii-xviii). With this term, Harvey describes the approach of anthropologists who are aware that their concepts contrast with the assumptions of early anthropologists. But this does not mean that scholars of the new animism always refute modern beliefs that nothing exists beyond the natural world, which is grounded in the philosophies, principles, methods, and conclusions of the sciences.

Animal spirits and animistic places

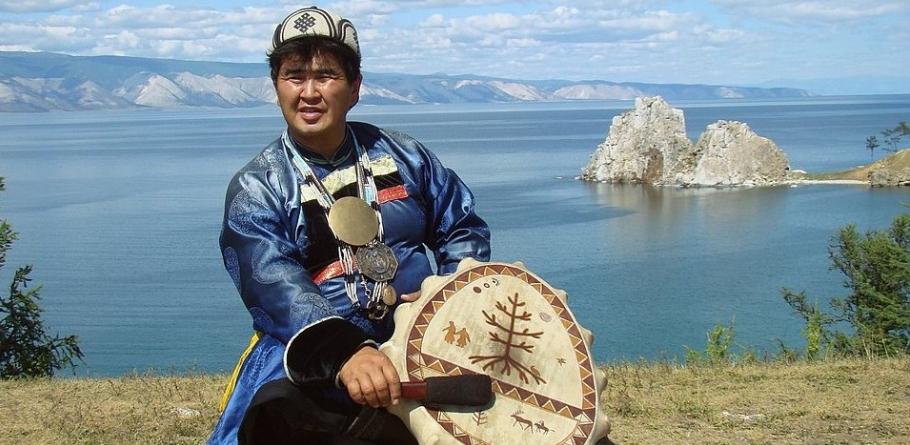

Studies of animism often point out the importance of animal spirits and places that are sacred or charged with animistic potentialities. Animal spirits refer to the spirits or souls attributed to animals that may be considered the seat of an animal’s consciousness and motivation. These studies show how animistic potentialities go beyond the human subject.

In animistic societies, animals frequently show their sentience, awareness, and motivation to act through their relationships to human beings. Diverse ways of relating to animal sentience are revealed by the ways that hunters and shamans in particular treat animal spirits. Siberian Eveny, for example, consider that the spirits of the animals they hunt in the harsh Arctic climate are master-parents to all humans. As parents, animal spirits may take pity on their children – which include Eveny persons – by offering themselves up as food to eat. A hunted animal does not make this sacrifice lightly, but ‘will “give itself up” only when the relation between hunter and prey is hierarchical’ – that is, when the human being needs to eat meat to survive (Willerslev & Ulturgasheva 2012: 55). But like parents, animal spirits are manipulated by Eveny, who trick them into giving themselves up to justify their acts of killing. To this end, hunters seek to establish ‘social contact’ with prey animals in a way that makes them appear vulnerable and child-like (Willerslev & Ulturgasheva 2012: 53). This is no easy task, since Eveny hunters acquire a ‘closed body’ with age that protects against attacks from the spirits of game animals. Hunters therefore must ‘re-open’ their bodies to mimic a child or use a child as ‘bait’ to attract a game animal that will pity the hungry child (Willerslev & Ulturgasheva 2012: 55). The child’s first hunt is organised around this tactic, in which the animal is attracted into close range by the child so the adult hunter can kill it. Then the hunter tasks the child with carrying the prey home on the back of a guardian reindeer, which wards off revenge from the animal’s spirit. While the animal’s spirit will pity the child and its guardian reindeer, both of which it considers to be its children, it may take revenge on the adult hunter for tricking it into giving itself up. Thus, the Eveny hunter implores the animal’s spirit after the kill that, ‘“you came to me out of your own free will, please have pity on us and do not harm us”’ (Willerslev & Ulturgasheva 2012: 55).

Conversely, among the Waorani of Amazonian Ecuador, revenge killings can be carried out on shamans who purportedly use animal spirits to conduct witchcraft (High 2012: 130). Waorani fear these killings, which can set in motion a dangerous cycle of deaths that may continue even after the errant shaman has died. Here, the logic of animal consciousness and motivation is different to that found among the Eveny. Since the shaman’s body ‘is inhabited by his adopted jaguar-spirit (meñi)’ at night, when it may attack and kill any named persons, Waorani warn each other against speaking with shamans during this dangerous time. Note that, unlike Eveny who trick animal spirits and plead with them not to take revenge, Waorani jaguar-spirits must be avoided at all costs. Their danger is compounded by the fact that Waorani shamans relate to jaguar-spirits like adopted children who will reciprocate care to their masters. Thus, when Waorani carry out revenge killings, they may find that the shaman’s ‘orphaned jaguar-spirit continues to live and kill people out of sadness and anger for its adopted father’ (High 2012: 130).

Consciousness and motivation in animistic societies is attributed not just to animals, but also to certain places. For example, Yup’ik residents of the Bering Sea coast consider that the ocean has eyes, sees everything, and does not like it when persons fail to follow the traditional abstinence practice of avoiding the waterfront after a birth, death, illness, miscarriage, or first menstruation (Fienup-Riordan & Carmack 2011: 269). Since the ocean brings disasters on people when it is upset, Yup’ik consider that it is best to wait until early spring before visiting it after one of these events. Spring is the season when grebes arrive and defecate in the water; it is also when ringed seals come and their blood soaks the ocean as predators attack. According to Yup’ik hunters, these events make ‘the makuat [ocean’s eyes] close and become blind’ so that the hunters can safely approach the waterfront again (Fienup-Riordan & Carmack 2011: 270).

Similarly, consciousness and motivation can be found in the fires of sacred hearths, which must be treated with respect as spirits reside in and around them. Among the Nenets tundra dwellers of the Siberian Yamal peninsula, women of reproductive age do not cross through the sacred space by the fireplace or hang clothes to dry above it that would be worn on the lower part of their bodies (Skvirskaja 2012: 151). Nenets men, however, store their possessions in this sacred space that serves as the place for hosting respected visitors. The Nenets fireplace reveals ‘the capacity of “things” to objectify some forms of gender relations at the expense of others’ (Skvirskaja 2012: 152).

Moreover, in animistic societies, places may be imbued with memory. Certain burial sites for Daur Mongolian shamans in northeast China have been covered by stone cairns known as ovoo, where Buddhist rituals now attract ‘all manner of princes, dignitaries and foreigners’, while drawing upon the memories and powers of both the shamanic spirits and Buddhist deities that were imbued in these locales (Humphrey with Onon 1996: 133). In a related light, the Western Apache of North America consider that certain locations contain memories and the wisdom to help people to make the right decisions. To Western Apache, a ‘visually unique’ place is like ‘a watertight vessel’ that holds ‘wisdom, [which] like water, is basic to survival’ (Basso 1996: 76). Since ‘wisdom sits in places’, they learn to memorise wisdom-filled stories about wisdom-filled places that can help them to address problems in a measured way (Basso 1996: 67).

Animism in early anthropology

Building upon the findings of historians, folklorists, travellers, traders, missionaries, and expedition members about the religious lives of peoples around the globe, Edward B. Tylor introduced the study of animism within anthropology. Although the term ‘animism’ can be traced to the Latin anima for breath, life, or spirit, Tylor borrowed it from George Ernst Stahl, an eighteenth-century chemist and physician, who proposed that the spirits or souls of living beings or things control physical processes in the body. Like Stahl, Tylor wanted to discuss the relationship between the soul and all forms of life. However, Tylor set out to shift the meaning of animism to encompass what he called ‘the groundwork of the Philosophy of Religion’ (1977 [1871]: 426). According to Tylor, animism is a form of religion in which the spirits and souls of humans and other beings are considered necessary for life. As Tylor was interested in the origins of religious views and how they develop over time, he hypothesised that persons adopt an animistic sensibility when reflecting on ‘the differences between a living body and a dead one’ as well as on ‘those human shapes which appear in dreams and visions’ (1977 [1871]: 428). He illustrates how human spirits appear in dreams or visions through numerous examples, like this one of the Zulu in Southern Africa:

the Zulu may be visited in a dream by the shade of an ancestor, the itongo, who comes to warn him of danger, or he may himself be taken by the itongo in a dream to visit his distant people, and see that they are in trouble; as for the man who is passing into the morbid condition of the professional seer, phantoms are continually coming to talk to him in his sleep, till he becomes, as the expressive native phrase is, “a house of dreams” (Tylor 1977 [1871]: 443).

According to Tylor, experiences such as these suggest that human beings have a soul that can appear to them. Through his extensive catalogue of dreamt phenomena, Tylor showed that persons dream of animal souls (1977 [1871]: 467-74), plant souls (1977 [1871]: 474-6), and even the souls of objects (1977 [1871]: 477, see also 478-80). On this basis, he suggested that persons who attribute souls to human beings, animals, plants, or objects gradually consider that the soul is not only a vital force to specific beings but is pervasive throughout the cosmos and imbued in all beings. Thus, he argued that the souls of humans, animals, plants, and objects survive death and bodily decay in an animistic cosmos, while inhabiting a world that is populated with spirits and deities (Tylor 1977 [1871]: 426).

Tylor championed the social evolutionary approach in anthropology that suggested that people progress from a ‘primitive’ stage of social life, in which they try to control the world around them with magical or religious practices, towards a so-called ‘modern’ life based on the philosophies, principles, and conclusions of science (1977 [1871]: 26-35). The influence of social evolutionism waned in anthropology in the early twentieth century, as anthropologists started to undertake their own fieldwork and obtained findings that cast serious doubt on the idea that societies represent levels of linear human progress. Despite extensive criticisms of it, social evolutionism never entirely disappeared from anthropology or from popular understandings in Euro-American societies about human cultures. Moreover, since Tylor presented his study of animism as evidence for the social evolutionary approach, the two became synonymous for some time. However, it is possible to study animism without the comparative evolutionary angle. Contemporary anthropological approaches show that modern technologies and science are also incorporated into animistic worlds.

Contemporary approaches and the ‘new animism’

In the shamanic journeys of the Chewong hunter, gatherer, and shifting cultivators of the Malaysian rainforest, new items of technology and ‘some species previously not thought of as people, may reveal themselves as such’ (Howell 2016: 63). Technological items can become people in the Chewong world through the assistance of shamans, who use the same word to refer to their spirit-guides and their consciousness. Thus, shamans ‘who have established a permanent relationship with a spirit-guide (ruwai) can send their consciousness (ruwai) on a journey into space [… where] any being or object may appear as a conscious being’ (Howell 2016: 63). Japanese airplanes, for example, became recognised as new spirit-guides that have consciousness after they flew over Chewong forests during World War II. A Chewong shaman’s song, still sung today, ‘refers to the ruwai of Japanese airplanes’ (Howell 2016: 63). In a not dissimilar way, several American pilots who crashed into the Liangshan mountains of Southwest China and were rescued by the Nuosu, a Tibeto-Burman pastoral and agricultural group, have been incorporated into their animistic creation epic known as the ‘Book of origins’. As folklorist Mark Bender and Nuosu poet Aku Wuwu explain, these WWII pilots and the early twentieth century French, English, and American explorers who visited the Liangshan highlands appear to have been lumped together in this Nuosu animistic myth, which contains recent additions on the ‘Foreigners’ lineage’ and ‘Migrations of foreigners’ (2019).

Recent works on animism, such as these, suggest that a broad understanding of different life-worlds and relationships is needed when we reflect upon what is substantively ‘real’ in an animistic world. It is in this spirit that Kathleen Richardson (2016) has introduced the concept of ‘technological animism’, which describes cases where the boundaries between literature and technoscience are crossed in the production and reception of robots. Like many other robots, the famous ASIMO (Advanced Step in Innovative Mobility) was made by Honda in Japan to resemble children so that its human creators and owners would engage with it as a cute, non-threatening, and childlike being. This marketing strategy was particularly important for roboticists in Euro-America ‘to counteract popular notions that robots are threatening to humanity and hyper-sophisticated’ (Richardson 2016: 115). Revealingly, the appeal of childlike robots to their Euro-American or Japanese owners resonates with the appeal of the childlike ‘open bodies’ that Eveny hunters present to the spirits of game animals so that they will pity them and give themselves up.

Relating to other beings as though they were kin is, then, a pervasive theme in current studies of animism (Bird-David 1999, 2018). While some relationships may be conceptualised in a parent-child form or ‘in an idiom of siblingship’, as among the Bentian of Indonesian Borneo (Sillander 2016: 171), it is not uncommon to find that kinship terms are extended to other-than-human beings or things in animistic societies, which may also share a common point of origin with humans (Brightman, Grotti & Ulturgasheva 2012: 8). But to stand the test of time, animistic relationships to other beings or things often need to be maintained. Thus, among the Bidayuhs of Sarawak, Malaysian Borneo, young Christians who wanted to move away from the animistic sensibilities of their parents have chosen to forget (or never properly learn) how to relate to animistic spirits, which ‘were deemed more forgiving of plain ignorance of the rules than of absent-minded transgressions’ (Chua 2009: 338).

What these studies suggest is the importance not only of thinking about different animisms in the plural, but of recognising – as Morten Pedersen suggests for peoples across North Asia, from Siberia to Mongolia – that animistic sensibilities often only come into focus in the right circumstances, contexts, and moments (2001: 415-20). A person may need certain faculties, such as an imaginative ‘openness’ to the world, to perceive the animistic sensibilities of other beings and things (Ingold 2006: 11-2, see also 18-9; 2013: 739, see also 741-2). Religious specialists, such as shamans, are often attributed with ‘inspired’ qualities that enable them to perceive animistic sensibilities that remain imperceptible to ordinary persons (Humphrey with Onon 1996). ‘Astonishment’ (Ingold 2006, 2013) or ‘wonder’ (Scott 2014) have thus become leitmotifs among scholars who seek to show how persons perceive and relate to animistic beings, things, forces, and experiences.

Much of the expansive thinking in the new animism is traceable to Alfred Irving Hallowell’s 1930s fieldwork among the Berens River Ojibwe of North America, which was punctuated by lively vignettes about the supernatural Thunder Birds, called pinési, which are giant birds that create thunder by clapping their wings. In his 1960 study of ‘Ojibwa ontology, behavior, and world view’, Hallowell invites anthropologists to rethink their life-worlds and those of animistic societies on the basis of his Ojibwe research. Hallowell ‘deeply identified’ with the animistic sensibilities of the Ojibwe and advocated that anthropologists routinely identify with their interlocutors as a way of enriching their anthropology and lives in general (Strong 2017: 468). His study shows that Ojibwe do not attribute animistic qualities to all beings or things at all times, but that they are open to finding that some beings or things may have animistic qualities in certain moments. Thus, Hallowell observes that while some Ojibwe have seen certain stones move in ceremonies, stones usually do not move and many people do not see them move. Similarly, he gives the story of an Ojibwe boy who claimed to have seen a Thunder Bird during a heavy storm – a story that was at first received sceptically by his parents because seeing ‘other-than-human persons’ is not a common Ojibwe experience. Ultimately, this sighting of the Thunder Bird was accepted when ‘a man who had dreamed of pinési verified the boy’s description’ (Hallowell 1960: 32; cited also in Strong 2017: 470). Revealingly, the boy’s parents were persuaded not by the fact that the Thunder Bird was identified by two different persons, but by the fact that the dreamer had perceived the same qualities in pinési as their son had seen during the thunderstorm. Ojibwe consider that people are especially open to perceiving animistic beings in dreams, where they routinely encounter them. Thus, the astonishing similarity between the inspired visions of a Thunder Bird seen by the boy during the storm, and later in another man’s dream, is what convinced his parents.

Animism as an ontology

As Pauline Turner Strong observes, Hallowell’s Ojibwe study presaged ‘an ontological return’ in contemporary anthropology, which brought a renewed focus to principles of animation and questions of being (2017: 468). While animism (and Tylor’s approach to it) fell out of fashion in anthropology after the 1920s, the interest in animistic sensibilities remained vibrant, as Hallowell’s 1930s fieldwork attests. Ethnographic studies documented animistic ways of being and continued to fill the shelves of anthropology and other disciplines, albeit often without using the term ‘animism’ again until the 1990s, when it regained popularity. This does not mean that ethnography always took the lead in anthropological studies on ontologies, some of which have instead been built upon philosophical or theoretical considerations inspired by ethnography (compare to Scott 2013).

Philippe Descola’s ‘fourfold schema of ontologies’ – comprised of animism, totemism, analogism, and naturalism – provides a vocabulary for discussing the kinds of worlds that anthropologists envision philosophically, theoretically, and in the light of ethnographic fieldwork (2014: 275; see also 2013). In Descola’s terms, the quintessential animistic ontology is a world characterised by ‘a continuity of souls and a discontinuity of bodies’ between humans and nonhumans (2014: 275). Each animistic being has a shared interior quality, such as a soul or vital life force. But Descola suggests that there are different kinds of bodies in any given animist world, such as the human body or the body of specific animals, plants, objects, and even spirits whose ‘bodies’ may be composed of an airy, wraith-like, or translucent substance. This difference in bodies makes for different kinds of animist beings, each of which has a soul and ‘possess[es] social characteristics: they live in villages, abide by kinship rules and ethical codes, they engage in ritual activity and barter goods’ (Descola 2014: 275).

According to Descola, there are important differences between animistic, totemic, analogic, and naturalistic ontologies. Totemic ontologies are common in Oceania, where persons and nonhuman beings share the same interior quality, such as a soul, and the same bodily substance, such as a physicality inherited through kinship to other-than-human totemic ancestors. By contrast, Descola suggests that analogic ontologies are common south of Siberia, in parts of Asia where persons and nonhuman beings do not share the same interior quality or the same bodily substance. Animal domestication is a hallmark of analogic ontologies because the use and consumption of animals lends itself to the view that the interior and bodily qualities of humans and nonhumans are different. Finally, naturalistic ontologies are common across Euro-America, where persons and nonhuman beings do not share the same interior quality, such as a soul, but do share the same bodily substance, namely a physicality traceable to taxonomies of species and evolutionary lines of descent.

Not everyone agrees with Descola’s approach. There have been famous debates, for example, between Descola and Eduardo Viveiros de Castro on animism and perspectivism (Latour 2009; Turner 2009: 27). Viveiros de Castro (1998, 2004) introduced ‘perspectivism’ as a term that puts a new spin onto what Descola calls animism. Drawing upon ethnographies of Amerindian peoples in Amazonia, Viveiros de Castro suggests that all beings in a perspectival ontology can adopt a human perspective, albeit under certain circumstances that are conducive for them doing so. Whereas Descola considers that animism (and its variant, perspectivism) is one kind of ontology that scholars can analyse and classify from an ‘objective’ and naturalist viewpoint, Viveiros de Castro proposes that perspectivism is a ‘bomb’ that shakes the foundations of the naturalism on which Descola’s scheme is based. Seen in this light, perspectivism is a kind of philosophy that makes possible an entirely different anthropology shaped by indigenous concepts. Thus, Viveiros de Castro argues against Descola’s naturalist view that animism (or perspectivism) only involves humans perceiving animals to have human and social qualities. He suggests instead that ‘animism is not a projection of substantive human qualities cast onto animals’ (Viveiros de Castro 1998: 477). Since Amazonians consider that animistic beings, such as animals, perceive themselves to be human, Viveiros de Castro holds that any animistic being that puts itself ‘in the position of subject, sees itself as a member of the human species’ (1998: 477).

Although Viveiros de Castro has critiqued Descola for generalising animism in a way that does not account for ethnographies of perspectivism, other anthropologists of Amazonia observe that Viveiros de Castro’s theory of perspectivism is not always ethnographically apt among Amerindian peoples. If we return to a discussion of the Waorani, we see that they do not neatly fit the profile of a perspectival ontology that tends ‘to describe the “predator” perspective as denoting a universally human perspective, [because] in everyday life Waorani people often identify themselves as “prey” to outside aggressors – whether in the form of jaguars, spirits, or human enemies’ (High 2012: 132). Unlike the perspectival groups discussed by Viveiros de Castro, Waorani consider that being a predator ‘is antithetical to proper human sociality’ (High 2012: 138). Casey High suggests that the Waorani view may reflect a new morality, brought on by missionary settlement, in which men are no longer ‘said to be actively trained as killers’ and where ‘openly engaging with jaguar-spirits poses too great a threat to the present ideal of “community” (comunidad)’ (2012: 140). People’s worlds can change over time in response to missionary conversion, social change, and a reflexive questioning of the parameters of one’s morality, which throws doubt on the prospect of viewing entire geographic regions as home to just one ontology, such as perspectivism.

Notwithstanding this, the oeuvres of Descola and Viveiros de Castro have been field-setting with good reason. They have provided new platforms for the comparative study of animism, while opening up vibrant conceptual fora for discussing the resonances between animism, perspectivism, and in some cases also totemism (Pedersen 2001; Willerslev & Ulturgasheva 2012; Århem 2016). Viveiros de Castro’s work on perspectivism has inspired a volume dedicated to exploring perspectival ontologies across Inner Asia (Pedersen, Empson & Humphrey 2007). Similarly, Descola’s study has led to the recent proposal of the altogether new ontological schema of ‘homologism’, based on Chinese divination, the I Ching, and a Daoist philosophy in which persons and nonhuman beings share the same interior quality and the same bodily substance. In homologism, interior quality and bodily substance are distilled into ‘a single energy-substance, qi, […] knowable via the observation of natural patterns and phenomena’ (Matthews 2017: 266). While this criteria of shared interior quality and bodily substance aligns with Descola’s criteria for totemism, William Matthews proposes that the term homologism better suits the profile of the Chinese ontology, and indeed, of any world that is predicated upon ‘shared intrinsic characteristics rather than analogies’ (2017: 265). Thus, he suggests that homologism ‘logically displaces Totemism as the structural counterpoint to Analogism’ in Descola’s schema (Matthews 2017: 265).

Animistic blending, blurring, and contradictions

Recent work on ontology has stimulated a re-envisioning of the kinds of beings that might populate any animist cosmos. ‘Hybridity’ is a recurrent theme among contemporary anthropologists, whose approaches to ‘chaos’ (Scott 2005) or the ‘fuzzy boundaries’ (Pedersen & Willerslev 2012) between the body and the soul evoke landmark studies on the agency and life force of technological items in transnational science (Latour 1993; Latour & Franke 2010). Bruno Latour (1993) showed that technological items may at first appear to be machines without the agency or life force of human beings. But on closer inspection, machines may take on the qualities of nonhuman hybrids with agency, vitality, a life force, and personhood. Examples of hybrids that an anthropologist might envision in animistic terms range from the part-human, part-machine beings known as ‘cyborgs’ (Haraway 1991 [1985]) to the ‘cosmic theatre’ of ‘outer space’ that hosted the joint travels of US astronauts and Soviet cosmonauts (Battaglia 2012: S76). However, Richardson’s study of technological animism, where robots are treated like children, suggests pushing past ‘the emphasis on hybridity and relationalities between persons and things [which] diminishes human subjectivity in these processes [… since] while humans may interact with things like robots that trigger thoughts, feelings, and behaviors, their interactions are mediated through human socialities’ (2016: 122).

What makes these concepts of hybridity, chaos, or fuzzy boundaries useful, then, is that they give a vocabulary for the ways in which animistic and other ontologies blend and blur in real life, thus leading to contradictions or giving rise to contexts in which more than one ontology may be operative. It is instructive in this regard to see that Eveny hunters live in a world where both totemism and animism are operative. The Eveny concept of an open body is actually totemic, as it is based on the principle that animals and persons with open bodies share the same bodily substances and interior qualities (Willerslev & Ulturgasheva 2012: 54). Eveny manipulate this totemic sensibility during the hunt by using children as bait, who lure prey into close range for a kill. But rather than reciprocating this totemic sensibility, hunters relate to prey with an animistic sensibility, that is, as animals with a different bodily substance that is edible. Acknowledging the fuzzy boundaries between ‘concepts’ such as totemism and animism, then, gives pause for thought on how they might become formative to fresh ways of envisioning anthropology and the world at large (Corsín Jiménez & Willerslev 2007).

The serious and humorous sides of animism

Some key anthropological approaches suggest that animism is not always taken seriously. As Willerslev observes, it is possible that ‘underlying animistic cosmologies is a force of laughter, an ironic distance, a making fun of the spirits, which suggests that indigenous animism is not to be taken very seriously at all’ (2013: 42). Yukaghir hunters are not averse to joking about the careful post-hunt handling of their prey to prevent an animal’s spirit from retaliating. Thus, an elderly hunter who, according to the post-hunt custom, crowed like a raven while removing a dead bear’s eyes with his knife was only momentarily shocked to hear a fellow hunter call to the bear, ‘Grandfather, don’t be fooled, it’s a man, Vasili Afanasivich, who killed you and is now blinding you!’ (Willerslev 2013: 51). Moments later, the elderly hunter burst out laughing and completed the work mirthfully with his hunting partner. On yet another occasion, Yukaghir hunters bought a plastic doll and treated it as an idol, feeding it fat and blood while bowing to it and calling out, ‘Khoziain [Russian, “spirit-master”] needs feeding’ (Willerslev 2013: 51). Later, they explained this parody with the quip, ‘[w]e are just having fun’ or the concession that ‘[w]e make jokes about Khoziain because without laughter, there will be no luck. Laughing is compulsory to the game of hunting’ (Willerslev 2013: 51). Humour, after all, appears vital to Yukaghir hunting luck and success.

This playful sense of humour underpins a good deal of New Age animistic practices in Euro-American contexts (Lindquist 1997: 15-6, see also 180-2; Houseman 2016). As the urban Swedish shaman, ‘Marie Ericsson, an artist and a long-time neo-shamanic practitioner once expressed it, “if the sacred does not bear being humoured, it is not sacred enough for me”’ (Lindquist 1997: 180). Reflecting on her interlocutor’s comment, Galina Lindquist adds that ‘the sense of wonderment, and the magical freedom of play, together with the communitas, and with the flow experienced by the performers and the audience, is what makes neo-shamanic practices at their peak moments so fulfilling’ (1997: 181).

If humour, wonder, and play lie at the heart of animistic practices, then it is well-worth considering the effects that the imagination and creativity have in a variety of animistic worlds. Imaginative thinking underpins what I and Mireille Mazard call an ‘animism beyond the soul’, which throws light on the ‘hyper-reflexive’ relationships between anthropologists, their interlocutors, and the animistic beings or forces in their cosmos (Swancutt & Mazard 2016: 2-5). Seen in this light, anthropological thinking may be shaped by interlocutors who have become anthropologically-savvy through formal study or by informally ‘apprenticing’ off of the anthropologists they know. Key concepts in our disciplinary history, including animism, can be playfully cycled through a ‘reflexive feedback loop’ in which interlocutors offer anthropologically-inspired reflections upon their worlds to anthropologists, whose thinking in turn is informed by the conceptual work done by their interlocutors (Swancutt & Mazard 2016: 3, see also 6-7 and 10-1). When this happens, the ludic side to animism (Swancutt 2016: 80, see also 86-9) may inform not only ethnographic analysis, but also the imaginative collaborations between anthropologists and their interlocutors that have been the hallmark of anthropology (Chua 2015; Chua & Mathur 2018).

Conclusion

Ethnographies around the world show that animism is a way of relating and attributing sentience to other beings, forces of nature, things, and even technological items. This entry has explored anthropological approaches to animism, from envisioning it as a philosophy of religion to building upon distinct philosophical, theoretical, and ethnographic sources that suggest animism may be more than a distinct sensibility, tendency, or style of engaging with the world. It may be an ontology in its own right.

Animism is approached from numerous directions in anthropology. It is considered to be an immanent rather than transcendent form of sentience. It is a way of revealing and sometimes manipulating the consciousness, motivation, memories, and powers of animal spirits, animistic places, and items of technology. As an ontology, animism may blend and blur with other ontologies, opening it up to contradictions, humour, creativity, imagination, inspiration, and reflexive awareness. Due to the diverse forms of animism worldwide, anthropologists have asked whether certain animistic groups may have undergone a history of diminution or disenchantment, which made them only attribute certain beings with an animistic sensibility. They also relate to animism in distinct ways, as scholars who are not animists, as scholars who advocate identifying with animists, or as scholars who are animists themselves.

Cutting across these varied approaches are competing visions of how animistic life-worlds unfold through human, other-than-human, and beyond human sensibilities. These distinct visions raise important questions about how we might relate to animism as a particular sensibility that can be studied ethnographically, debated about as a philosophical and theoretical possibility, deeply identified with as a way of enriching one’s scholarship and life, or (possibly) taken up as a sensibility of one’s own. What these big questions do is shine a reflexive mirror onto our own humanity, pressing us to articulate what sentience is in the first place and why we relate to others in the ways that we do.

References

Århem, K. 2016. Southeast Asian animism: a dialogue with Amerindian perspectivism. In Animism in Southeast Asia (eds) K. Århem & G. Sprenger, 279-301. London: Routledge.

Basso, K.H. 1996. Wisdom sits in places: notes on a Western Apache landscape. In Senses of place (eds) S. Feld & K.H. Basso, 53-90. Santa Fe, N.M.: School of American Research Press.

Battaglia, D. 2012. Arresting hospitality: the case of the ‘handshake in space.’ Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 18(S1), S76-S89.

Bender, M. & A. Wuwu 2019. The Nuosu Book of origins: a creation epic from Southwest China. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Bird-David, N. 1999. ‘Animism’ revisited; personhood, environment, and relational epistemology.Current Anthropology 40(S1), S67-S91.

———2018. Size matters! The scalability of modern hunter-gatherer animism. Quarternary International 464(A), 305-14.

Brightman, M., V.E. Grotti & O. Ulturgasheva (eds) 2012. Introduction – animism and invisible worlds: the place of non-humans in indigenous ontologies. In Animism in rainforest and tundra: personhood, animals, plants and things in contemporary Amazonia and Siberia, 1-27. New York: Berghahn.

Chua, L. 2009. To know or not to know? Practices of knowledge and ignorance among Bidayuhs in an ‘impurely’ Christian world. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 15(2), 332-48.

———2015. Troubled landscapes, troubling anthropology: co-presence, necessity, and the making of ethnographic knowledge. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 21(3), 641-59.

———& N.Mathur (eds) 2018. Who are ‘we’? Reimagining alterity and affinity in anthropology. New York: Berghahn.

Corsín Jiménez, A. & R. Willerslev 2007. ‘An anthropological concept of the concept’: reversibility among the Siberian Yukaghirs. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 13(3), 527-44.

Descola, P. 2013. Beyond nature and culture (trans. J. Lloyd). Chicago: University Press.

——— 2014. Modes of being and forms of predication. HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 4(1), 271-80.

Fienup-Riordan, A. & E. Carmack 2011. ‘The ocean is always changing’: nearshore and farshore perspectives on Arctic coastal seas. Oceanography 24(3), 266-79.

Hallowell, I.A. 1960. Ojibwa ontology, behavior, and world view. In Culture in history: essays in honor of Paul Radin (ed.)S. Diamond, 19-52. New York: Columbia University Press.

Haraway, D.J. 1991 [1985]. A cyborg manifesto: science, technology, and socialist-feminism in the late twentieth century. In Simians, cyborgs, and women: the reinvention of nature, 149-81. New York: Routledge.

Harvey, G. 2017 [2005]. Animism: respecting the living world. London: Hurst & Co.

High, C. 2012. Shamans, animals and enemies: human and non-human agency in an Amazonian cosmos of alterity. In Animism in rainforest and tundra: personhood, animals, plants and things in contemporary Amazonia and Siberia (eds) M. Brightman, V.E. Grotti & O. Ulturgasheva, 130-45. New York: Berghahn.

Houseman, M. 2016. Comment comprendre l’esthétique affectée des cérémonies New Age et néopaïennes?. Archives de Sciences Sociales des Religions 174(2), 213-37.

Howell, S. 2016. Seeing and knowing: metamorphosis and the fragility of species in Chewong animistic ontology. In Animism in Southeast Asia (eds)K. Århem & G. Sprenger, 55-72. London: Routledge.

Humphrey, C. with U. Onon 1996. Shamans and elders: experience, knowledge and power among the Daur Mongols. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Ingold. T. 2006. Rethinking the animate, re-animating thought. Ethnos: Journal of Anthropology 71(1), 9-20.

——— 2013. Dreaming of dragons: on the imagination of real life. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 19(4), 734-52.

Latour, B. 1993.We have never been modern (trans. C. Porter). Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

——— 2009. Perspectivism: ‘type’ or ‘bomb’?. Anthropology Today 25(2), 1-2.

——— & A. Franke 2010. Angels without wings. A conversation between Bruno Latour and Anselm Franke. In Animism volume I, 86-96. Berlin: Sternberg Press.

Lindquist, G. 1997. Shamanic performances on the urban scene: neo-shamanism in contemporary Sweden. Stockholm: Stockholm Studies in Social Anthropology.

Matthews, W. 2017. Ontology with Chinese characteristics: homology as a mode of identification. HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 7(1), 265-85.

Pedersen, M.A. 2001. Totemism, animism and North Asian indigenous ontologies. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 7(3), 411-27.

———, R. Empson & C. Humphrey (eds) 2007. Special issue: perspectivism. Inner Asia 9(2), 141-348.

——— & R. Willerslev 2012. ‘The soul of the soul is the body’: rethinking the concept of soul through North Asian ethnography. Common Knowledge 18(3), 464-86.

Richardson, K. 2016. Technological animism: the uncanny personhood of humanoid machines. Special issue: animism beyond the soul: ontology, reflexivity and the making of anthropological knowledge. Social Analysis 60(1), 110-28.

Scott, M.W. 2005. Hybridity, vacuity, and blockage: visions of chaos from anthropological theory, Island Melanesia, and Central Africa. Comparative Studies in Society and History 47(1), 190-216.

——— 2013. The anthropology of ontology (religious science?). Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 19(4), 859-72.

——— 2014. To be a wonder: anthropology, cosmology, and alterity. In Framing cosmologies: the anthropology of worlds (eds) A. Abramson & M. Holbraad, 31-54. Manchester: University Press.

Sillander, K. 2016. Relatedness and alterity in Bentian human-spirit relations. In Animism in Southeast Asia (eds) K. Århem & G. Sprenger, 157-80. London: Routledge.

Skvirskaja, V. 2012. Expressions and experiences of personhood: spatiality and objects in the Nenets tundra home. In Animism in rainforest and tundra: personhood, animals, plants and things in contemporary Amazonia and Siberia (eds) M. Brightman, V.E. Grotti & O. Ulturgasheva, 146-61. New York: Berghahn.

Strong, P.T. 2017. A. Irving Hallowell and the Ontological Turn. In ‘Forum: voicing the ancestors II: readings in memory of George Stocking’ (ed.) R. Handler. HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 7(1), 461-88.

Swancutt, K. 2016. The art of capture: hidden jokes and the reinvention of animistic ontologies in Southwest China. Social Analysis 60(1), 74-91.

——— & M. Mazard (eds) 2016. Special issue: animism beyond the soul: ontology, reflexivity and the making of anthropological knowledge. Social Analysis 60(1), i-139.

Tylor, E.B. 1977 [1871]. Primitive culture: researches into the development of mythology, philosophy, religion, language, art and custom (vol. I). New York: Gordon Press.

Viveiros de Castro, E. 1998. Cosmological deixis and Amerindian perspectivism. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 4(3), 469-88.

——— 2004. Exchanging perspectives: the transformation of objects into subjects in Amerindian ontologies. Common Knowledge 10(3), 463-84.

Willerslev, R. 2007. Soul hunters: hunting, animism, and personhood among the Siberian Yukaghirs. Berkeley: University of California Press.

——— 2013. Taking animism seriously, but perhaps not too seriously?. Religion and Society: Advances in Research 4(1), 41-57.

——— & O. Ulturgasheva 2012. Revisiting the animism versus totemism debate: fabricating persons among the Eveny and Chukchi of north-eastern Siberia. In Animism in rainforest and tundra: personhood, animals, plants and things in contemporary Amazonia and Siberia(eds) M. Brightman, V.E. Grotti & O. Ulturgasheva, 48-68. New York: Berghahn.

Note on contributor

Katherine Swancutt is Senior Lecturer in the Anthropology of Religion and Director of the Religious and Ethnic Diversity in China and Asia Research Unit at King’s College London. She is the author of Fortune and the cursed: the sliding scale of time in Mongolian divination (2012, Berghahn) and co-editor of Animism beyond the soul: ontology, reflexivity, and the making of anthropological knowledge (2016, special issue of Social Analysis and 2018, Berghahn). She has written numerous articles on animistic and shamanic religion. www.swancutt.com

Dr Katherine Swancutt, Department of Theology and Religious Studies, King’s College London, Virginia Woolf Building, 22 Kingsway, London, WC2B 6LE, United Kingdom. katherine.swancutt@kcl.ac.uk